topic/grief

Gina Frangello,

Jenny Zhang,

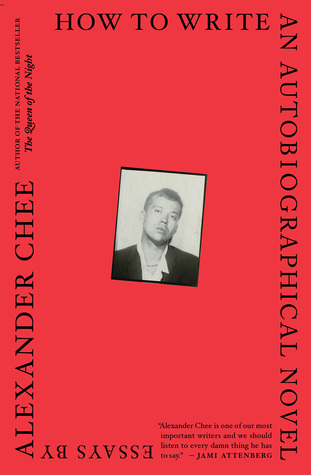

Alexander Chee,

Percival Everett,

Lucia Berlin

When an artist dies young there is always talk of the paintings unpainted, the books unwritten, which points to some imaginary storehouse of undone things and not to the imagination itself, the far richer treasure, lost. All of those works are the trail left behind, a path across time, left like the sun leaves gold on the sea: you can see it but you can't ever pick it up. What we lose with each death, though, is more like stars falling out of the sky and into the sea and gone. The something undone, the something that won't ever be done, always remains unendurable to consider. A permanent loss of possibility, so that what is left is only ever better than nothing, but the loss is limitless.

“Mother,” she said, as she jumped on the trampoline. “Mother, I didn’t want to leave you, but I had to go with Father into the mountains. Mother, you told me to take care of my brother and I let him fight and he lost his legs. Mother, I let you down. Mother, you said you wanted to die in my arms and instead I watched our house burn with you inside as I fled to the mountains. I told Father I wanted to get off the horse and die with you and he gripped me to his chest and would not let me get down. Mother, I would have died with you, but you told me to go. I should not have gone.”

I took a step toward her. Her eyes were open but they did not see me. In the dark, I thought I would always remember this night and be profoundly altered by having seen her this way. But it was like one of those dreams where you think to yourself while the dream is happening that you must remember the dream when you wake — that if you remember this dream, it will unlock secrets to your life that will otherwise be permanently closed — but when you wake up, the only thing you can remember is telling yourself to remember it. And after trying to conjure up details and images and coming up blank, you think, Oh well, it was probably stupid anyway, and you go on with your life, and you learn nothing, and you don’t change at all.

aaah this made ms cry

On Wednesday I glanced out the window and saw a shadow. It was high noon and sunny. A young bear had come down from the mountain. He had found the red sugar water of a hummingbird feeder and was sitting on his fat ass, lapping it up. The sight was a joyous one for me; it was the bear that Sarah had been looking for her entire life. I pushed her chair to the window. I looked at my daughter's empty eyes. I looked at the bear. It was so big, so real, so alive. I put my arms around my child and cried. "Please, see the bear, baby. Please."

At last, Death is starting to listen. Almost nightly now, my father dreams of his dead brothers. My mother and I rarely figure in his subconscious. In the dreams, his brothers are still young: Emilio playing the sax; Joe a mildly powerful bookie; Frank on the front porch smiling and waving with his grandkids. In one dream, my father is forcibly taken away on a wagon across a barren white landscape.

“I never took my father out to dinner,” he tells my mother, his voice thick with regret. “He worked himself to the bone for us and I never bought him a meal.”

“You were a young man,” my mother assuages. My paternal grandfather died before I was born. “You had your own life. You didn’t know he would die soon. You thought you had time.”

Mr. Tortorici is dead by now, too, of course.

Time stops when someone dies. Of course it stops for them, maybe, but for the mourners time runs amok. Death comes too soon. It forgets the tides, the days growing longer and shorter, the moon. It rips up the calendar. You aren’t at your desk or on the subway or fixing dinner for the children. You’re reading People in a surgery waiting room, or shivering outside on a balcony smoking all night long. You stare into space, sitting in your childhood bedroom with the globe on the desk. Persia, the Belgian Congo. The bad part is that when you return to your ordinary life all the routines, the marks of the day, seem like senseless lies. All is suspect, a trick to lull us, rock us back into the placid relentlessness of time.