inspo/dialogue

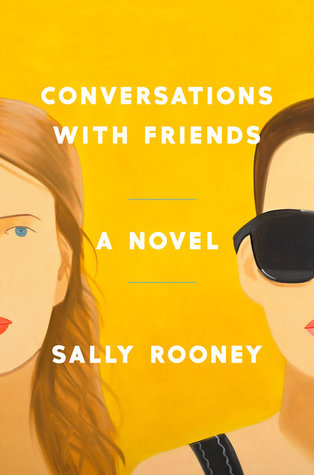

Sally Rooney,

Rachel Kushner,

Jennifer Egan,

Raymond Carver,

Jonathan Franzen,

Nick Hornby,

Viet Thanh Nguyen,

Annie Proulx,

Jonny Steinberg

good dialogue, with or without quotation marks

The restaurants and bars all had miniature Christmas trees and fake sprigs of holly in the windows. A woman went past holding the hand of a tiny blond child who was complaining about the cold.

I waited for you to call me, I said.

Frances, you told me you didn't want to see me any more. I wasn't going to harass you after that.

I stopped randomly outside an off-license, looking at the bottles of Cointreau and Disaronno stacked up in the window like jewels.

love the way she sandwiches the convo in between observations

(ofc, the real revelation here is the miscommunication)

In 1994, I was 19 years old. I’d dropped out of college. I had a job parking cars at a hospital in downtown Louisville. I lived in a one-room apartment and my neighbor beat on his wife. He beat her pretty loud.

One night I called the cops. The switchboard operator said: Is he still whipping her? If he’s not whipping her when we get there, we can’t just take him in. Unless she files a complaint. And she won’t do that.

No ma’am.

That’s right. Now you wait until he’s beating her real good and you’re sure he’s going to keep on her for some ten or fifteen minutes. That way when we get there we can haul his ass to jail. Otherwise we leave him. He’s going to think she called us. And he’s going to kill her. I mean to death. And that’s on you. You understand that?

Later that week, I was trying to get some sleep. His wife was crying. The children were crying. Something, maybe a lamp, broke against the wall. I’d gotten hammered on red wine. I don’t know what I was thinking when I stumbled through the backyard and around our building to their apartment, and I didn’t have to find out: a thin man I’d never seen before was already standing there, knocking on their door with his left hand. His right hand held a gigantic revolver.

He looked at me and smiled. You’re a good boy, he said, but go on, now.

I went back to my apartment and I turned up the record player as loud as it would go. Pharoah Sanders and Roy Haynes. Pretty loud.

i love how spare this writing is

[...] we could see a garden with green things the size of baseballs hanging from the vines.

"What's that?" I said.

"How should I know?" she said. "Squash, maybe. I don't have a clue."

"Hey, Fran," I said. "Take it easy."

She didn't say anything. She drew in her lower lip and let it go. She turned off the radio as we got close to the house.

noted for the emotion (petulance, tension) communicated solely through dialogue, not adjectives

After a time, Olla came back with it. I looked at the baby and drew a breath. Olla sat down at the table with the baby. She held it up under it arms so it could stand on her lap and face us. She looked at Fran and then at me. She wasn't blushing now. She waited for one of us to comment.

"Ah!" said Fran.

"What is it?" Olla said quickly.

"Nothing," Fran said. "I thought I saw something at the window. I thought I saw a bat."

"We don't have any bats around here," Olla said.

"Maybe it was a moth," Fran said. "It was something. Well," she said, "isn't that some baby."

obviously ugly baby

I asked after Arthur Mitchell.

‘He and his wife live in Perth,’ I was told. ‘With their daughters.’

‘How are they?’ I asked.

A long silence.

‘Nobody here has been in touch with them for years.’

The silence continued another moment or two, the distance between these people and Arthur Mitchell filling the room.

‘Who farms there now?’ I asked.

In retrospect, the trip to the city had been a ridiculous idea. After all, the beginning of the beginning of the end had started on a trip to New York. On the train, he tried to engage Miranda with complaints about the departmental budget cuts, but all she wanted to talk about was this wonderful Wittgenstein she was learning about in her college course. ‘“Every sign by itself seems dead. What gives it life? In use it lives. Is it there that it has living breath within it? Or is the use its breath?”’ she said, an eager sheen in her eye. ‘Well?’

‘I didn’t think I needed to respond,’ he said. ‘It doesn’t seem to have to do with real life at all.’

‘Maybe when you say you didn’t think you needed to respond, you didn’t need to. Maybe I needed you to respond.’

‘Is this still philosophy or do you just talk like that now?’

‘Jesus, Bill.’

‘What?’ He looked at her looking out the window. From the side, her lips were two red jelly beans. He could absolutely bite them. This was real life: lips like jelly beans! Historical facts! He was a man of events, not ideas, a historian, a knower, not a philosopher. ‘We’ll be there soon,’ he said.

‘When is soon?’

‘Twenty minutes.’

‘That’s not what I meant,’ she said. ‘When you imagine soon, the word soon, what do you see in your mind? When is it?’

‘I feel like I can’t say anything without it becoming a fucking discussion anymore,’ he said.

‘Lucky we’re going to a play then,’ she said. They didn’t talk for the rest of the ride.

lmao

"Only guy I know who still owns a beeper."

McRae looked up over his half-moons with a wide-open, undimmed enthusiasm that made even his gentlest son fear for him.

"Really? A lot of the guys at work have 'em."

“I never met a girl who rides Italian motorcycles,” he said. “It’s like you aren’t real.”

He looked at my helmet, gloves, my motorcycle key, on his bureau. The room seemed to hold its breath, the motel curtain sucked against the glass by the draft of a partly opened window, a strip of sun wavering underneath the curtain’s hem, the light-blocking fabric holding back the outside world.

He said he wished he could see me do my run, but he was stuck at the motel, retiling a rotten shower.

“It’s okay,” I said. I was relieved. I felt sure that this interlude, my night in Stretch’s bed, shouldn’t overlap with my next destination.

“Do you think you might come through here?” he asked. “I mean, ever again?”

I looked at the crates of tools and the jumbled stack of the owner’s son’s bicycle collection, some of them in good condition and others rusted skeletons with fused chains, perhaps saved simply because he had ample storage space in poor Stretch’s room. I thought about Stretch having to sit in a parking lot all night instead of lie in his own bed, and I swear, I almost decided to sleep with him. I saw our life, Stretch done with a day’s work, covered with plaster dust, or clean, pulling tube socks up over his long, tapered calves. The little episodes of rudeness and grace he’d been dealt and then would replay in miniature with me.

I stood up and collected my helmet and gloves and said I probably wouldn’t be back anytime soon. And then I hugged him, said thanks.

He said he might need to go take another shower, a cold one, and somehow the comment was sweet instead of distasteful.

Later, what I remembered most was the way he’d said my name. He said it like he believed he knew me.

awww this is cute

“When I got out, I thought, okay, unlike a lot of my friends, I know what the inside of a prison is like. Most people don’t even know what the outside of a prison is like. They’re kept so out of sight. You only know signs on the highway warning you in certain areas not to pick up hitchers. While I know about confinement and boredom and midnight fire drills. Amplified orders banging around the prison yard like the evening prayer call from the mosques along Atlantic Avenue. I know pimento loaf. Powdered eggs. Riots. The experience of being hosed down with bleach and disinfectant like a garbage can. I know about an erotics of necessity.”

“Oh, baby,” the Duke of Earle said.

“There’s something in that. You think you’re one way — you know, strictly into women. But it turns out you’re into making do.”

“I am going to melt,” the duke said, “just puddle right in this booth. I had no idea—”

“I don’t want to disappoint you, Duke,” the friend said, “but I’d have to be in prison, and I don’t plan on going back.”

i love the vivid emotion conveyed in the duke's lines

“[...] He’s calling to those rabbits like they know their names and are going to be happy to see him. I’m thinking, isn’t he amazed by how quickly I got here? Isn’t he going to at least mention it? I was redlining his Jaguar. I pissed in a Dr Pepper bottle. When it was full I pissed in a potato chips bag. I broke the law. Gave up a night’s sleep. Forwent the tube socks at the truck stop.”

“Incredible self-control,” Sandro said.

“All in the name of doing Saul a favor. I mean, you try to help a person. He opens the car door and leans in the back and makes this sound. A wailing. High-pitched.”

“Oh, no,” Sandro said, and put his hands over his face, feigning a brace for disaster.

“Yeah, that’s right. Those goddamn rabbits were dead.”

“You forgot to check on them.”

“My job was transport. And I didn’t hear any complaints from back there. But I had the windows down and there was a lot of truck traffic — especially on the 10. I don’t know what happened. They just… died.”

incredible story