advice/writing

Patricia Highsmith,

Ursula K. Le Guin,

Mary Karr,

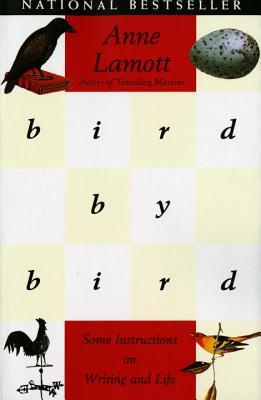

Anne Lamott,

David Foster Wallace,

Vijay Prashad,

George Saunders,

Alexander Chee,

Robert Hass

tips

You are going to love some of your characters, because they are you or some facet of you, and you are going to hate some of your characters for the same reason. But no matter what, you are probably going to have to let bad things happen to some of the characters you love or you won’t have much of a story. Bad things happen to good characters, because our actions have consequences, and we do not all behave perfectly all the time. As soon as you start protecting your characters from the ramifications of their less-than-lofty behavior, your story will start to feel flat and pointless, just like in real life. Get to know your characters as well as you can, let there be something at stake, and then let the chips fall where they may. [...]

Lastly: I heard Alice Adams give a lecture on the short story once, one aspect of which made the writing students in her audience so excited that I have passed it along to my students ever since. (Most of the time I give her credit.) She said that sometimes she uses a formula when writing a short story, which goes ABDCE, for Action, Background, Development, Climax, and Ending. You begin with action that is compelling enough to draw us in, make us want to know more. Background is where you let us see and know who these people are, how they’ve come to be together, what was going on before the opening of the story. Then you develop these people, so that we learn what they care most about. The plot—the drama, the actions, the tension—will grow out of that. You move them along until everything comes together in the climax, after which things are different for for the main characters, different in some real way. And then there is the ending: what is our sense of who these people are now, what are they left with, what happened, and what did it mean?

I honestly think in order to be a writer, you have to learn to be reverent. If not, why are you writing? Why are you here?

Let’s think of reverence as awe, as presence in and openness to the world. The alternative is that we stultify, we shut down. Think of those times when you’ve read prose or poetry that is presented in such a way that you have a fleeting sense of being startled by beauty or insight, by a glimpse into someone’s soul. All of a sudden everything seems to fit together or at least to have some meaning for a moment. This is our goal as writers, I think; to help others have this sense of—please forgive me—wonder, of seeing things anew, things that can catch us off guard, that break in on our small, bordered worlds. When this happens, everything feels more spacious. [...]

Annie Dillard has said that day by day you have to give the work before you all the best stuff you have, not saving up for later projects. If you give freely, there will always be more. This is a radical proposition that runs so contrary to human nature, or at least to my nature, that I personally keep trying to find loopholes in it. But it is only when I go ahead and decide to shoot my literary, creative wad on a daily basis that I get any sense of full presence [...]

Two things put me in the spirit to give. One is that I have come to think of almost everyone with whom I come into contact as a patient in the emergency room. I see a lot of gaping wounds and dazed expressions. Or, as Marianne Moore put it, "The world’s an orphan’s home." And this feels more true than almost anything else I know. But so many of us can be soothed by writing: think of how many times you have opened a book, read one line, and said, "Yes!" And I want to give people that feeling, too, of connection, communion.

The other is to think of the writers who have given a book to me, and then to write a book back to them. This gift they have given us, which we pass on to those around us, was fashioned out of their lives. You wouldn’t be a writer if reading hadn’t enriched your soul more than other pursuits. So write a book back to V. S. Naipaul or Margaret Atwood or Wendell Berry or whoever it is who most made you want to write, whose work you most love to read. Make it as good as you can. It is one of the greatest feelings known to humans, the feeling of being the host, of hosting people, of being the person to whom they come for food and drink and company. This is what the writer has to offer.

All that I know about the relationship between publication and mental health was summed up in one line of the movie Cool Runnings, which is about the first Jamaican bobsled team. The coach is a four-hundred-pound man who had won a gold in Olympic bobsledding twenty years before but has been a complete loser ever since. The men on his team are desperate to win an Olympic medal, just as half the people in my classes are desperate to get published. But the coach says, "If you’re not enough before the gold medal, you won’t be enough with it." You may want to tape this to the wall near your desk.

Style is a very simple matter; it is all rhythm. Once you get that, you can't use the wrong words. But on the other hand here am I sitting after half the morning, crammed with ideas, and visions, and so on, and can't dislodge them, for lack of the right rhythm. Now this is very profound, what rhythm is, and goes far deeper than words. A sight, an emotion, creates this wave in the mind, long before it makes words to fit it.

All right, so you shut the door, and you write down a first draft, at white heat, because that energy has been growing in you all through the prewriting stage and when released at last, is incandescent. You trust yourself and the story and you write.

[...]

Then it cools down and you cool down, and arrive, probably somewhat chilled and rueful, at the next stage. Your story is full of ugly, stupid bits. You distrust it now, and that's as it should be. But you still have to trust yourself. You have to know that you can make it better. Unless you're a genius or have extremely low standards, composition is followed by critical, patient revision, with the thinking mind turned on.

I can trust myself to write my story at white heat without asking any questions of it - if I know my craft through practice - if I have at least a sense of where this story's going - and if when it's got there, I'm willing to turn right round and go over it and over it, word by word, idea by idea, testing and proving it till it goes right. Till all of it goes right.

Consider the story as a dance, the reader and writer as partners. The writer leads, yes; but leading isn't pushing; it's setting up a field of mutuality where two people can move in cooperation with grace. It takes two to tango.

Fiction, like all art, takes place in a space that is the maker's loving difference from the thing made. Without that space there can be no consistent truthfulness and no true respect for the human beings the story is about.